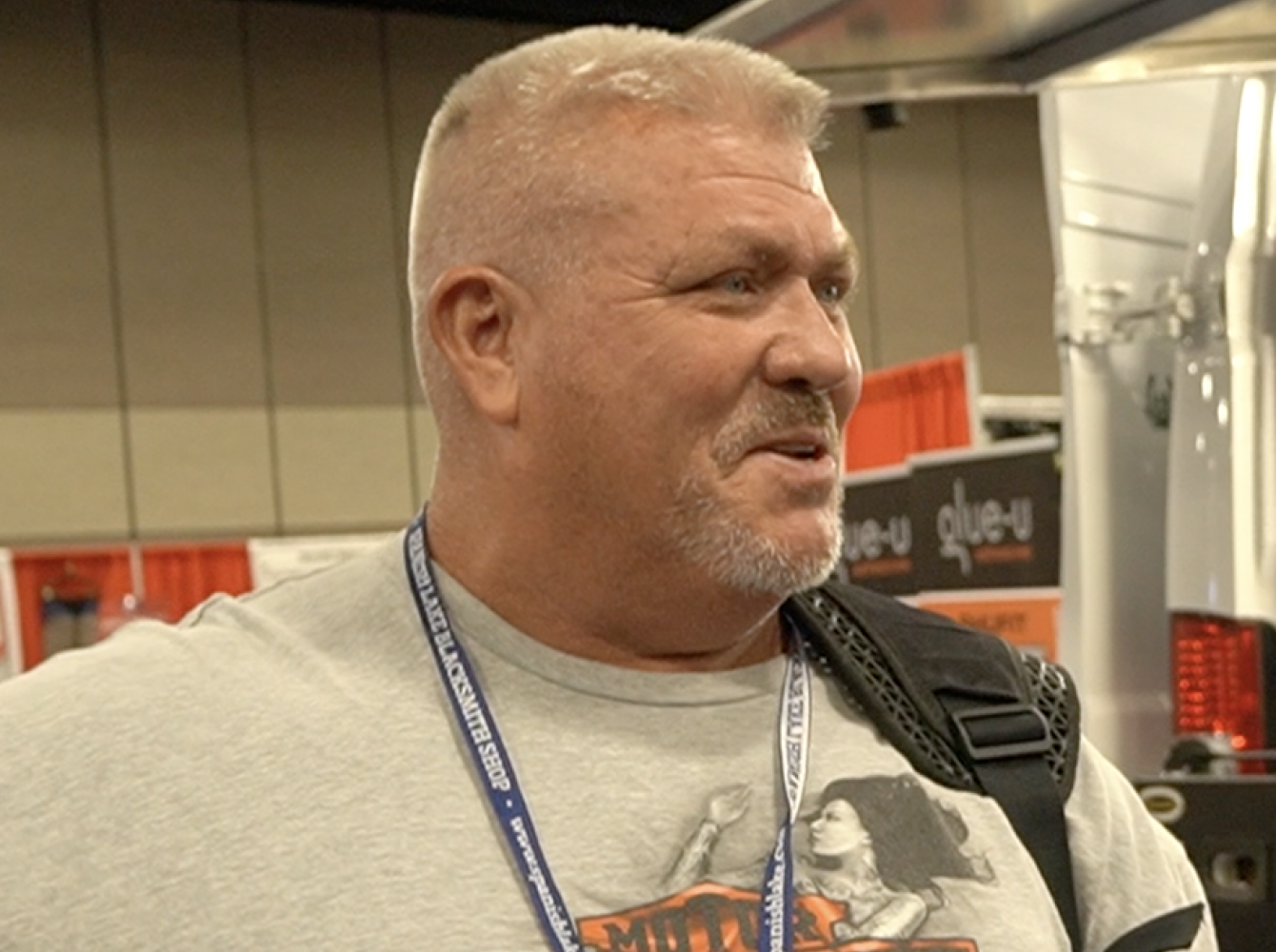

Lonnie Miller, CF

Lonnie Miller grew up in the sixties and seventies. But he carries with him the wisdom of generations.

An honors grad of the old school

When he was 15 years old in 1975, his grandfather asked Lonnie Miller, “What would you do if you never got paid?” He answered, “shoe horses.” And his education began then and there.

It didn’t take a conventional route. Before he could learn about shoeing, his grandfather wanted him to learn about life. So, he took him to the local nursing homes to volunteer and talk to the residents. “They were on the wagon train or their family members were on the wagon train. And that’s where my knowledge started. Not only did I get educated by the older gentlemen, I also got educated by the ladies in the nursing home on how to date women properly and what’s expected of a young man.”

In 1978, he met Jerry Matthews in Osawatomie, Kansas. Miller is a big guy—he has worked as a bodyguard—but he chokes up when talks about the debt he owes Matthews. “Jerry’s a Vietnam vet and he’s pretty much responsible for my career. I did my apprenticeship with him for five years. We did everything. Jerry’s always been an anchor for me. Whenever I run into a problem, I always revert back to Jerry, my mentor, even to this day. I’m 62. Jerry’s, I believe, 73.”

In 1989, Miller moved to Texas, where for a year he worked a full-time job from midnight to 7 A.M. and built his horseshoeing business during the day. He met a lot of people and made some great connections, one of which—a bodyguard gig for musician Dave Alexander—led to a three-year gig as a spokesman for the Toyota T100 pickup (now the Tacoma). Toyota was looking for a clean-cut guy in an old-fashioned trade. The minute they saw Miller on film, they knew they had their man.

Images from a TV commercial promoting Toyota’s T100 truck.

Over time, he built a strong business, with an emphasis on hunters and jumpers, keeping over 125-150 horses sound and, in many cases, competitive. His clients are thriving, and he’s had most of them for over twenty years. A hunter whose front feet he shod with steel Mustad LiBeros—aluminum is dominant in hunting—recently attained the number one junior ranking in the country. Today, Miller is married to his wife Miss Nancy, and together they have a blended family of 7 children, with his oldest daughter Melissa being a roper. He and his wife have 10 grandchildren. He’s a happy man.

“It’s all about the horse.”

For Miller, everything comes down to the horse and he’s emphatic that farriers should be horsemen. Knowledge of the horse informs his horseshoeing. He admires great work in the forge but doesn’t let him distract him from his focus on the hoof and everything it carries.

“We do this for the horse. I make people mad. I will not ask for permission. I will ask for forgiveness. And I will do for the horse what’s best for the horse.”

He was a horseman when he was still a boy, delivering The Dallas Morning News and The Fort Worth Star on horseback. In his teen years, he would spend summers with his grandpa and uncles in Kansas. “We went out and bought 20 to 30 wild horses a summer. I’m talking wild. We had to run ‘em in. And that was my job and my brother’s job. We had to teach these horses to ride, pack, and drive by the end of the summer. We farmed with them. The only thing we didn’t do with them was bale the hay. We developed a lot of horsemanship skills by doing that.”

He looks at every horse’s confirmation. He notices their gate and stride and power and, if they’re jumpers, how high they jump.

“My uncle, Norman Watts, used to buy cattle for the King Ranch back in the 50s and 60s. He’s the one that taught me the confirmation of the horse. He’s the one who taught me how the horse is put together and how they’re supposed to move.”

“Jerry Matthew taught me stay out of the way of a horse—don’t do anything to the horse that’s going to cause any problems. My philosophy is: Look at the confirmation. Shoe the horse. Stay out of his way.”

Lonnie consulting with a client and her horse.

“Whipping begins when the knowledge ends.”

True to this philosophy, he's careful not to make unnecessary adjustments or overtrim a hoof. And he doesn’t find it necessary to forge shoes from scratch. Instead, he makes careful adjustments to existing shoes.

“I took the Equi-Librium which is a really good shoe. Where guys used to have to add a pad to wedge up the fetlock, I ground the shoe even more and I can pick a fetlock up a full inch.”

“I developed what I call a stifle shoe. I grind the medium aspect of the toe off. So the horse breaks square over his hocks and stifles. I’m saving my horses an injection a year and I’m saving my customers a couple thousand a year.”

Lonnie shaping a Mustad LiBero front on the anvil.

His work and his life are informed by the kind of education that is passed down through generations. It took him some time to realize what his father meant when he said, 'The whippings begin when the knowledge ends.' It means that you’re not smart enough to figure out how to get around that problem without using force. You need to get educated and become a horseman.”

He’s proud that all but one of his many apprentices have gone on to farrier work.

Miller quotes something he heard at the nursing home, back in the 70s. “There’s more knowledge dying every day in this nursing home than they’ll ever have in a library.”

Stories from Skunk Run and Branson

Miller and his Mustad Rep were talking at a Grant Moon presentation and realized they may have played in the same neighborhood, with the same kids, when they were young—a place called Skunk Run in Ottawa, Kansas.

He calls his Mustad rep the best salesperson in the world because he convinced him to buy his samples. He was talking up the Heller eXcel rasps. It turns out that he didn’t have any left, so Miller bought some.

The rasps sold themselves. His favorite is the blue tang, Heller eXcel Original. “It creates a very smooth finish and it’s wide to work with the big warmblood feet. With ponies, just one or two swipes makes them look great.” He was also quick to point out that, joking aside, whenever he has a question, Seaton is right on it.

Besides the Equi-Libriums, he relies on LiBeros. “They’re easy-to-shape shoes. When you heat them in the fire, you can shape them in less than 10 moves.” He works with Delta and Mustad concave nails.

He has a clear retirement strategy—shoeing until 70, moving into a condo he bought in Branson, Missouri, and getting a job driving the tram at Silver Dollar City that takes you from the parking lot to the front gate.

"I wanna be that dude who tells you to get on or get off."

"Last November, I went there, fell in love with the place. I really enjoyed the guys on the tram. I wound up helping more elderly people on and off than they did. When a lady with a baby in a stroller fell, I wound up catching the baby before it hit the concrete. My brother-in-law said I didn’t think you could move that fast and I said I didn’t either."

As you might expect, Miller’s still old school. “I open my wife’s car door every time she gets in or out of the truck. Can’t enter a building without me opening the door. And if it’s raining I get the umbrella and hold it over her.” Those lessons from the nursing home stuck.